Preface

The Open Container Initiative (OCI) defines open industry standards for containers. OCI currently includes three specifications:

- Runtime Specification (runtime-spec)

- Image Specification (image-spec)

- Distribution Specification (distribution-spec)

I will introduce the three OCI specifications in a series of articles, along with related software and tools, such as the widely used container runtime runc. This article will introduce some important concepts in the Container Image Specification (image-spec). Below are the two earlier articles about the runtime specification:

Overview

You may know that when running a container using tools like Docker or Podman, a container image is required. You may also know that this image contains all the dependencies (libraries, files, etc.) needed to run the software inside the container. However, you may not yet have looked into how container images are structured. This article will explain that.

OCI defines a standard for container images, hosted in a GitHub repository (see Reference [1]). The purpose of defining the container image standard is:

To enable the creation of interoperable tools for building, transporting, and preparing a container image to run.

How a Container Image is Structured

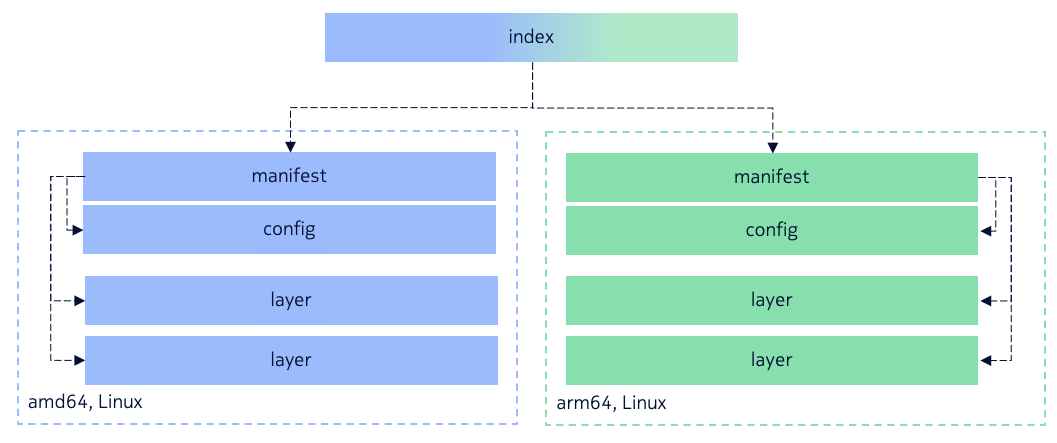

An OCI container image is composed of a manifest, an index (optional), a set of filesystem layers, and a configuration. The manifest, index, and configuration are JSON files. Each filesystem layer is a tar archive (optionally compressed with gzip or zstd). The diagram illustrates the relationships between these components.

Key points:

- The image index is optional, as it mainly supports multi-platform images. An index contains a set of manifests, each corresponding to a platform. If the image targets only a single platform, no index is needed.

- The image manifest is the entry point for an image of a specific platform. It corresponds to a specific architecture and operating system. It contains references to the image configuration and filesystem layers. The manifest itself does not contain the data but provides the information needed to find them.

- The image configuration contains parameters such as startup commands, environment, history, architecture, and OS. This configuration is used when an OCI runtime (e.g., runc) creates a container from the image.

- The image filesystem layers represent the container’s root filesystem. Stacking these layers in order produces the full filesystem.

An Example

Let’s see an example of how this works in practice.

We use skopeo to download the BusyBox container image from Docker Hub and convert it into OCI format. Skopeo is a very useful tool for working with container images and registries. I may write another article about common container image tools later.

$ skopeo copy docker://busybox:latest oci:busybox

$ tree busybox

busybox

├── blobs

│ └── sha256

│ ├── 79c9716db559ffde1170a4faf04910a08d930f511e6904c4899a1f7be2abfb34

│ ├── 9c0abc9c5bd3a7854141800ba1f4a227baa88b11b49d8207eadc483c3f2496de

│ └── af47096251092caf59498806ab8d58e8173ecf5a182f024ce9d635b5b4a55d66

├── index.json

└── oci-layout

Here, index.json is the image index mentioned earlier. Let’s inspect it:

$ cat index.json | jq .

{

"schemaVersion": 2,

"manifests": [

{

"mediaType": "application/vnd.oci.image.manifest.v1+json",

"digest": "sha256:79c9716db559ffde1170a4faf04910a08d930f511e6904c4899a1f7be2abfb34",

"size": 610

}

]

}

It contains a set of image manifests. In this example, there is only one manifest.

Based on its digest, we can find it in the blobs directory. Let’s inspect that file:

$ cat blobs/sha256/79c9716db559ffde1170a4faf04910a08d930f511e6904c4899a1f7be2abfb34

{

"schemaVersion": 2,

"mediaType": "application/vnd.oci.image.manifest.v1+json",

"config": {

"mediaType": "application/vnd.oci.image.config.v1+json",

"digest": "sha256:af47096251092caf59498806ab8d58e8173ecf5a182f024ce9d635b5b4a55d66",

"size": 372

},

"layers": [

{

"mediaType": "application/vnd.oci.image.layer.v1.tar+gzip",

"digest": "sha256:9c0abc9c5bd3a7854141800ba1f4a227baa88b11b49d8207eadc483c3f2496de",

"size": 2155907

}

],

"annotations": {

"org.opencontainers.image.url": "https://github.com/docker-library/busybox",

"org.opencontainers.image.version": "1.37.0-glibc"

}

}

This image manifest contains references to the configuration file and filesystem layers. We see that BusyBox has only one filesystem layer, compressed as a gzip tarball. Let’s check the configuration file and the filesystem layer:

$ cat blobs/sha256/af47096251092caf59498806ab8d58e8173ecf5a182f024ce9d635b5b4a55d66

{

"config": {

"Cmd": [

"sh"

]

},

"created": "2024-09-26T21:31:42Z",

"history": [

{

"created": "2024-09-26T21:31:42Z",

"created_by": "BusyBox 1.37.0 (glibc), Debian 12"

}

],

"rootfs": {

"type": "layers",

"diff_ids": [

"sha256:59654b79daad74c77dc2e28502ca577ba8ce73276720002234a23fc60ee92692"

]

},

"architecture": "amd64",

"os": "linux"

}

The configuration file includes information such as the startup command, history, architecture, and operating system. The BusyBox filesystem layer is gzip-compressed. If we decompress it, we can see the root filesystem, which becomes the runtime environment of a container based on this image.

$ file blobs/sha256/9c0abc9c5bd3a7854141800ba1f4a227baa88b11b49d8207eadc483c3f2496de

blobs/sha256/9c0abc9c5bd3a7854141800ba1f4a227baa88b11b49d8207eadc483c3f2496de: gzip compressed data, from Unix, original size modulo 2^324505600

$ mkdir rootfs

$ tar xvfz blobs/sha256/9c0abc9c5bd3a7854141800ba1f4a227baa88b11b49d8207eadc483c3f2496de -C rootfs

$ tree -d rootfs

rootfs

├── bin

├── dev

├── etc

│ └── network

│ ├── if-down.d

│ ├── if-post-down.d

│ ├── if-pre-up.d

│ └── if-up.d

├── home

├── lib

├── lib64 -> lib

├── root

├── tmp

├── usr

│ ├── bin

│ └── sbin

└── var

├── spool

│ └── mail

└── www

Conclusion

You can always refer to the official OCI image-spec (Reference [1]) for details. I hope this article gave you a conceptual understanding of container images. Of course, there are many other interesting topics, such as:

- How image filesystem layers are transformed into the root filesystem of a container.

- How container engines like containerd and runc handle images in practice. (Note: runc does not handle images directly—it only handles filesystem bundles converted from images, as discussed in earlier articles).

I hope to cover these topics in future articles. If you want to know specific details in this area, please let me know.

References

- [1] image-spec